One of the most exciting chess battles was the 1966 Chess Championship between Tigran Petrosian and Boris Spassky. Tigran was the World Champion at the time, having won the 1963 championship decisively against the very famous Mikhail Botvinnik. In my chess studies, there was a time period when I went carefully through many of the World Chess Championship games in hopes of learning something. The “Iron Tiger,” Tigran did not disappoint. I learned an interesting lesson, both in life and chess.

Leading up to this match was an amazing Interzonal chess event held by the Dutch Chess Federation. The up-and-coming superstar Bobby Fischer was in one of his many arguments with the International Chess Organization, known as FIDE. They bent to some of Bobby’s demands, but he still refused to play. The Russians had such a dominance at the time that one of the rule changes was to not to allow all the finalists from the Interzonal event to come from the same country.

This was an exciting time in chess. The old chess guard was still in control of the game, but new challengers were on the horizon. There were a lot of issues being debated at the time, and it was interesting to see how the political struggles between countries, the personal disputes among some of the players, and the desire to make the game more competitive so other countries would stay engaged. The games were exciting, and the stage was set to determine who would go up against Tigran Petrosian for the 1966 World Chess Championship.

The interzonal ended up with 3 Russian GMs and 1 Danish GM (Bent Larsen) as four candidates to compete for the final position. Long story short, the final round was between the former world champion, Mikhail Tal, and the new rising star, Boris Spassky. Tal was the fan favorite. He played stronger now after some health challenges and was considered a remarkable genius. His attacking style and daring moves made for some exciting chess games. To this day, he remains a favorite, tremendously influencing the chess community. However, Spassky kept these games from becoming Tal fireworks shows and slowly brought the gameplay to a dull six draws in a row. Perhaps Tal grew tired because, in the end, Spassky beat him three games in a row to become the candidate that would take on the World Champion.

The games began with a packed audience to watch. All the world’s most famous chess players watched Spassky try to defeat the Iron Tiger. There would be a total of 24 games between the two, with Tigran eventually outlasting Spassky and beating him by 1 point. Tigran would keep his title. My focus now is to discuss Game Seven of this championship. This is the game where I started to understand a fundamental concept in chess, but more importantly, in my own life.

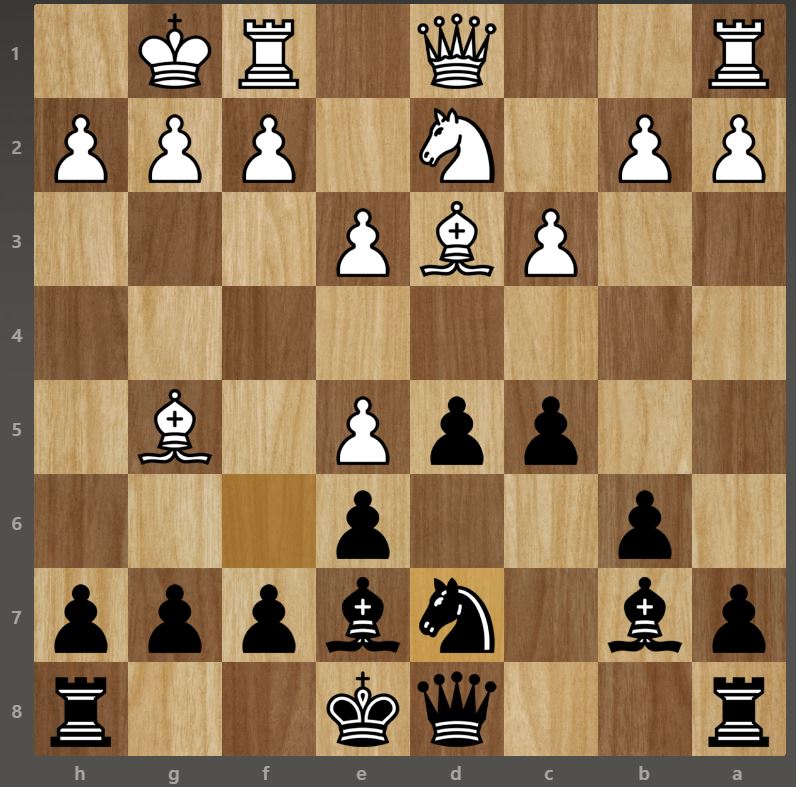

As you probably know, statistically, winning with the white pieces is easier. This is because white has the first move and starts the initiative. In this game, Petrosian had the black pieces. This game ended up being an attacking game, for which Spassky was often to do. This game was known as the Torre Attack also called the Colle System. This game follows the common gameplay up until move 11. Here, Spassky makes a different move, preferring to keep his dark square bishop. This game position (Game Position 1) is where at move 10. dxe5 Nd7. Tigran retreats the Knight to a defensive position and at the same time attacks the e pawn.

What is notable about this is that Tigran always seems to elect very tight, closed positions where all his pieces are tightly guarded. Note the structure of Tigran’s pawns and pieces compared to Spassky’s. This slow, deliberate play was what Tigran became known for. Slow defensive play. However, there is more going on than that, which is where the lesson comes in. After a few more moves, we end up in this position (Game Position 2):

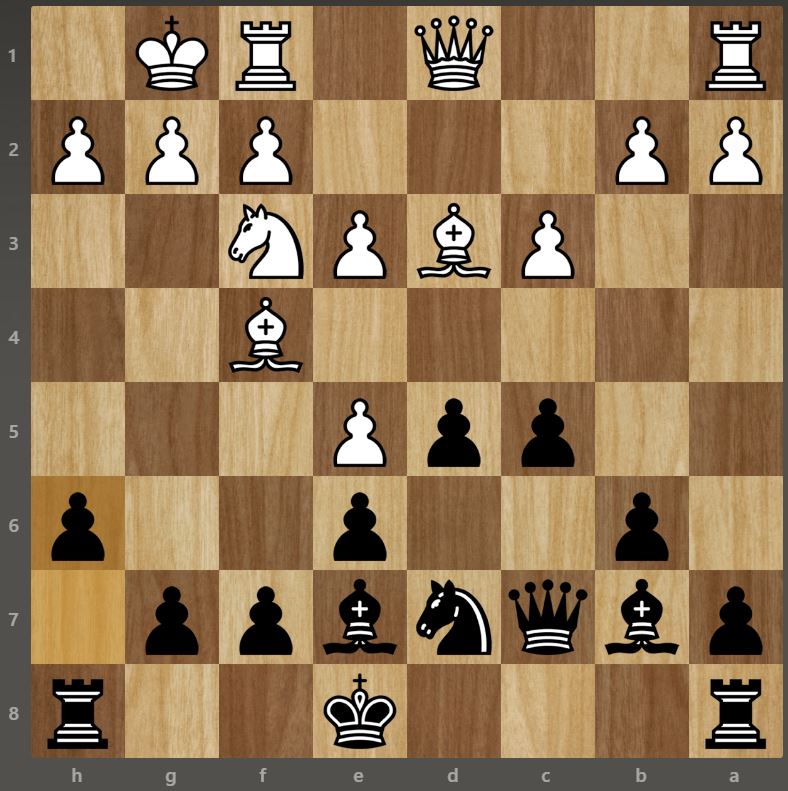

You will see there is a battle going on for the weak e-pawn. This is typical in this position, and in this case, Spassky chose to position his Knight on f3 to add more support to that forward pawn. Tigran’s response is to advance his pawn to h6. Clearly, the intent was to threaten the bishop on f4 but also slowly build his defensive position and start to squeeze his opponent. Later the dramatic moment will occur in this game, but what happens first is the slow and methodological narrowing down of the white pieces’ ability to gain space.

The game continues, and Tigran continues to apply pressure to this dark square bishop. Each move by Tigran accumulates a slight advantage in space and in position. This is subtle, but it is happening. Each move improves the situation by black ever so slightly. Here is the position after move 17 (Game Position 3).

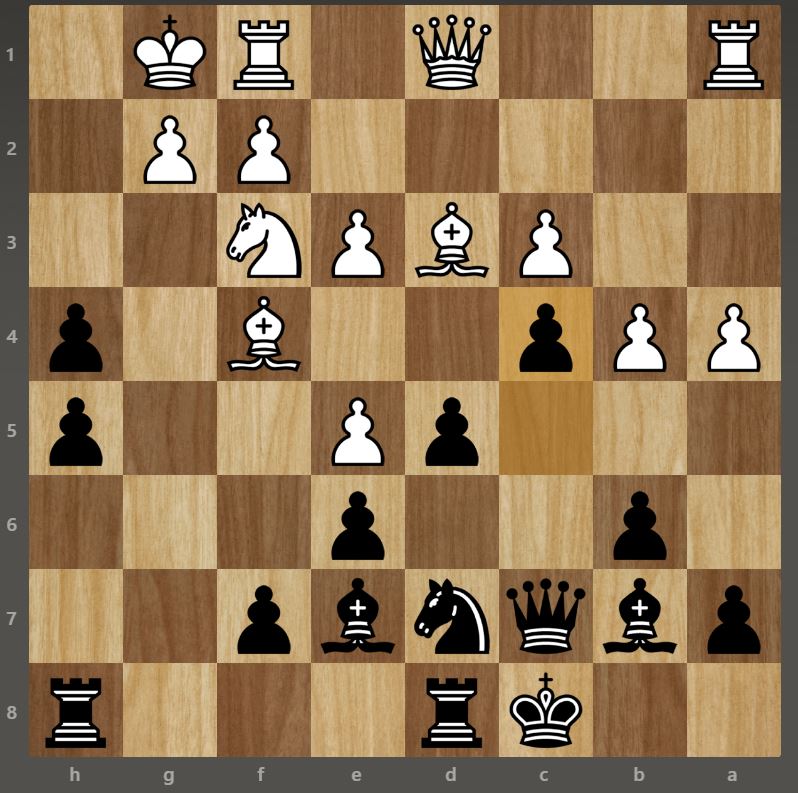

Notice a few things that have happened now. Tigran did push that black bishop around, and that is how the pawns ended up being on the h-file. Spassky knew his space was getting constricted, so he was attempting to create space on the a and b files by moving the pawns up. Tigran just moved his pawn to c4, and note the effect. The position gets closed off. The black bishop is left forever defending the e pawn and the white square bishop now has to retreat and is largely ineffective. Black is accumulating small advantages, all the while leaving most of the pieces on the board well-defended. After some more moves, here is where we are at after move 22 (Game Position 4):

Tigran just made the move b5, after Spassky’s attempt to advance the a pawn further. This is once again a highly defensive move. This completely seals off any real threat of attack on that side of the board. Meanwhile, Tigran is building pressure on the g file with the doubled-up rooks aiming down on the g2 pawn. Notice all the things going on here on that side of the board. Pressure is being applied and there are some real threats going on here. Spassky does not seem to be in any immediate danger, but what is going on is that black is growing in small advantages. Move by move, Tigran is gaining an advantage. Incremental improvement. A powerful chess engine would give Tigran a pawn advantage at this point of the game.

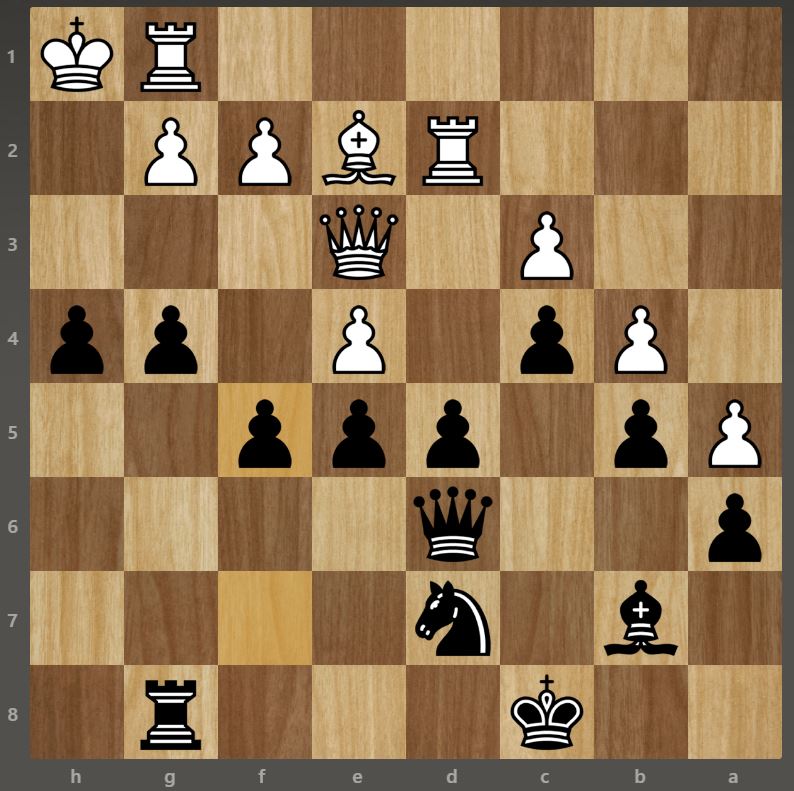

Now we come to the moment where the small incremental advantages become so powerful that Tigran can make a stunning and soul-destroying move. This move woudl like the chess world on fire and was probably the beginning of the end for Spassky in this championship. See this position (Game Position 5): Spassky just moved his knight to h2, fending off the nasty black rook and potentially freeing the white square bishop. The problem is that Tigran has built too much of an advantage at this point in the game. He is now allowed to take some risks. He can afford to do that because of the advantages that he has earned with his slow, yet cumulative play.

Can you spot Tigran’s next move? This is the moment where Tigran wins the game. He does not win right away, but he gains the equivalent of having two pawns on his opponent. In GM play, that type of advantage usually means game over. Look carefully! What move has Tigran been wanting to make this entire game? What move would he make now that would be a potential risk? Remember, this is the World Championship match. He is playing the new superstar from the Russian Botvinnik school. This younger man does not make mistakes, only precise play will beat him. So what do you do? What is your move?

Tigran chooses to take the e pawn with the knight! So, 24…. Nxe5! If you notice that that leaves the rook still under threat. So Spassky takes the knight with 25. Nxg4 hxg4 26. e4 Bd6. The game now shifts, the momentum is in favor of Petrosian. His small incremental improvements have led to this moment and now he has all the initiative. After move 30…f5, the game looks like this (Game Position 6):

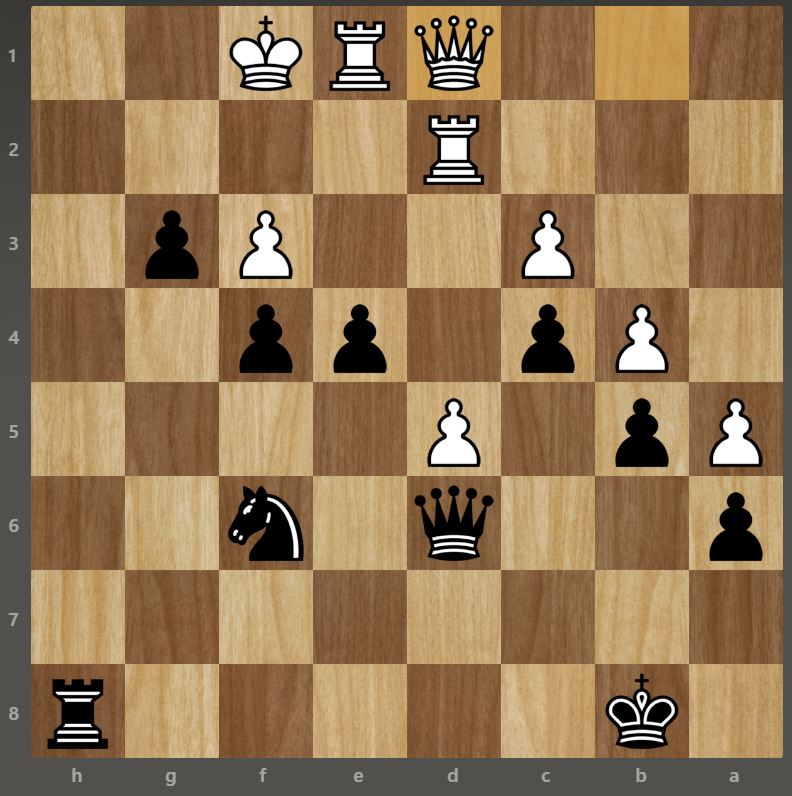

You can see the squeezing effect of Tigran’s play at this point in the game. He is slowly crushing Spassky, and has his pieces under control. Meanwhile, the black pieces have all the freedom and movement required. This starts to force Spassky to make tough decisions. Spassky attempts to penetrate the position with his Queen, but is quickly forced to retreat. The defensive play of Petrosian is just too strong. Finally, at the end Spassky has his Queen and Two Rooks sandwiched into the back ranks and the positional play of Tigran is so dominating, he can sacrifice yet another piece (Game Position 7):

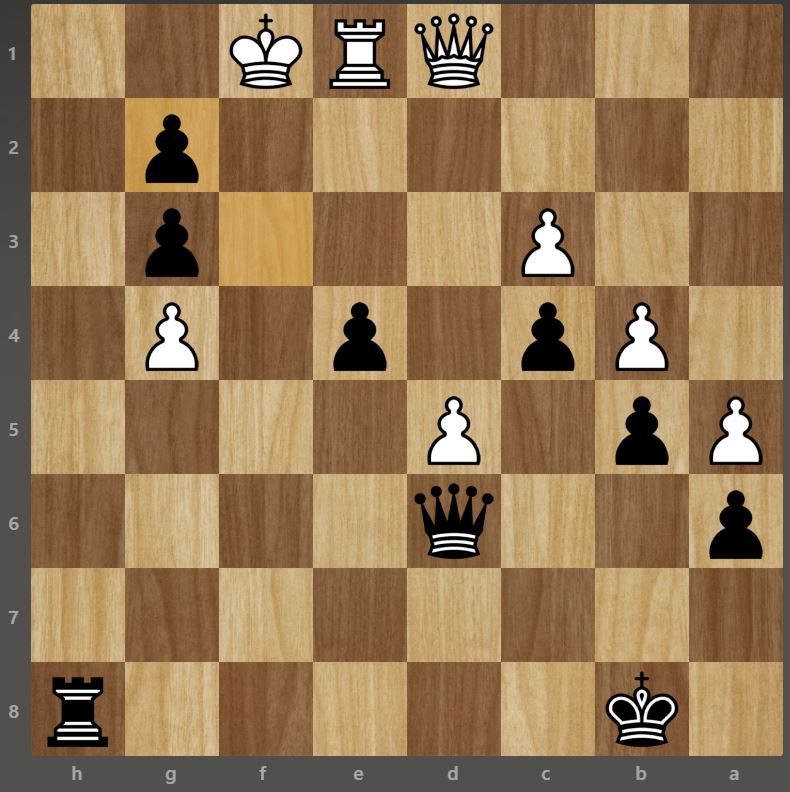

Now, Tigran plays 41…. Ng4. Even after this knight sacrifice, Spassky is forced to sacrifice a rook to stay alive. However, his defeat is all but certain. So he resigns. This is the look of the board after Spassky’s resignation (Game Position 8):

When I first studied this game, I came to a realization of how chess is supposed to be played. A contest in which you are slowly trying to build one small incremental improvement at a time. Once you reach a situation where that accumulation of benefits can be used, then you strike and push your advantage to hopefully win the game. I also made this connection in my own personal life. Far too often, I sought the quick win or the rapid climb to success. However, after gaining this understanding, I realized that life is much the same. We need to slowly improve, one increment at a time. Once we have accumulated enough, if we are fortunate, then we may have a chance to use that accumulation of benefits to do something amazing.

This game, and Petrosian’s methodical style, taught me that both chess and life are about patience and persistence. Just as Tigran built his position, move by move, we too must focus on small improvements in our lives. The key to success lies not in immediate triumph, but in the steady accumulation of advantages, waiting for the right moment to capitalize on them. Petrosian’s victory over Spassky was not won by a single move, but by his commitment to a strategy of incremental gains. And in life, as in chess, it is these small, thoughtful steps that lead to long-term success. This game stands as a reminder that the path to victory is often slow and deliberate, but ultimately, it is those who understand the value of patience who triumph in the end.