The Immortal Zugzwang Game is a gem from Copenhagen in March of 1923. Two great minds, Friedrich Sämisch and Aron Nimzowitsch, sat across from each other and created a position that has been studied ever since. You do not need to be a chess historian to feel the elegance of what unfolded. Pressure mounted, pieces took their places, and then the board went quiet. That quiet was the point. Nimzowitsch arranged a position where silence itself won.

Nimzowitsch mattered because he taught the world to value what is not obvious. Where others chased fast attacks, he studied the slow bonds that hold a position together. He wrote about blockades, about restraining pawn moves, about squeezing before striking. He championed ideas over immediate tactics, structure over spectacle. We remember him because he expanded the language of chess. After Nimzowitsch, players began to see the board not just as a battlefield of blows, but as a living system of pressure and possibility.

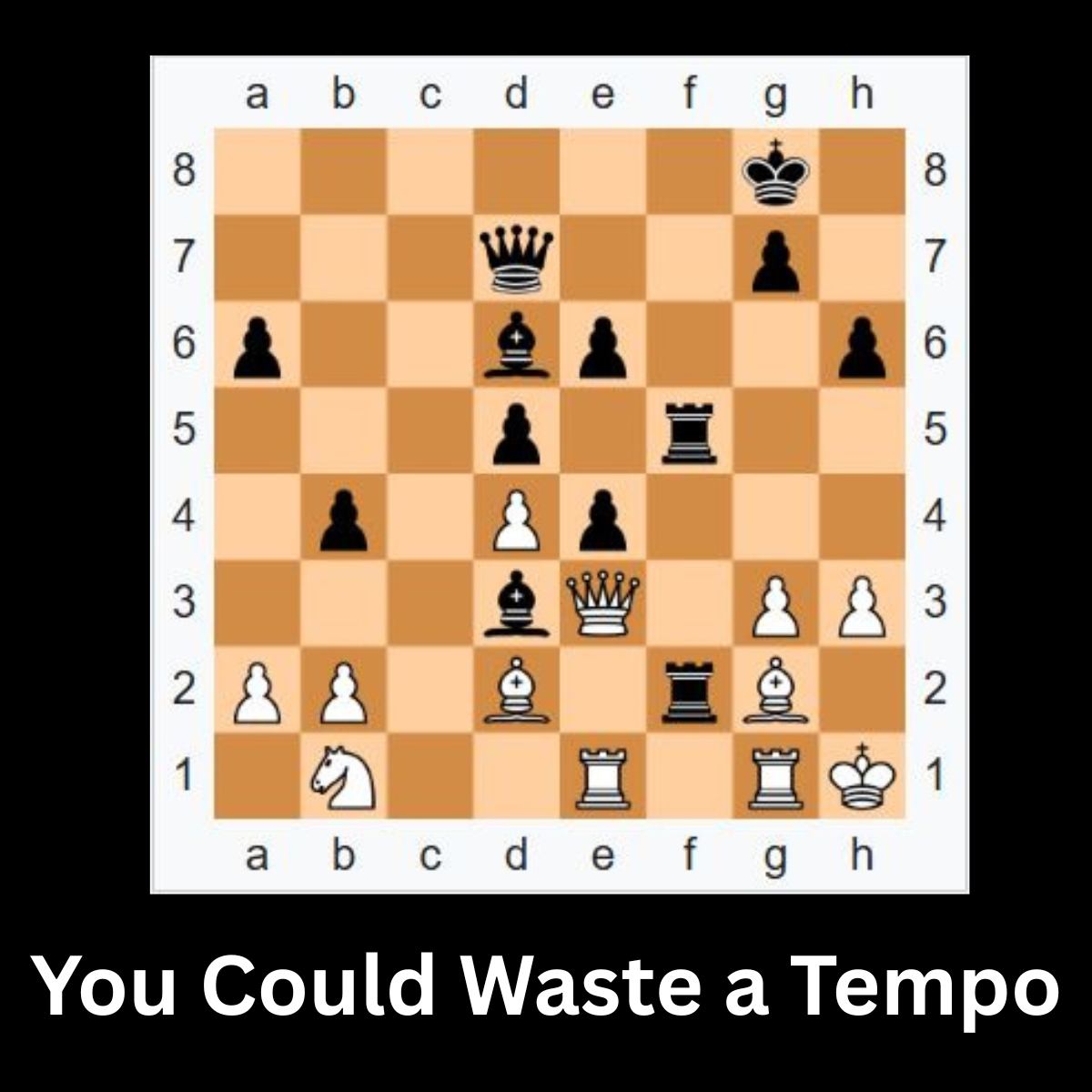

The ending in Copenhagen came suddenly, yet it had been prepared over many moves. Nimzowitsch engineered a scenario where any move that Sämisch made would worsen his position. Nimzowitsch could shift his king back and forth with safety, while Sämisch had to step on the rake. That is zugzwang. If Sämisch could have passed, he might have been fine. Chess does not allow that. You must move, even when any move is a mistake.

The heart of the trap was a surprising knight sacrifice. In the middle game, there came a moment with a dangerous pawn advance on the horizon. Instead of waiting for that pawn to surge, Nimzowitsch captured it and left his knight exposed on the edge of the board. Sämisch took the knight, as any reasonable player would. At first glance, it looked like a blunder. It was not. Nimzowitsch had exchanged a not productive piece for a position brimming with threats. He traded material for a web of constraints. This was the sort of thinking he was famous for, a willingness to give up what did not serve the plan in order to create a position that made the opponent’s choices collapse.

Chess players talk about tempo, about the initiative, about forcing moves that demand a reply. Yet there is a quieter wisdom as well. Sometimes you give up tempo on purpose. You make a waiting move. You let your opponent reveal their intentions. In the end game, this can be decisive. The player who must move may be the one who loses. The waiting move becomes the winning move, not because it dazzles, but because it refuses to be rushed.

There is a lesson here for life and business. Patience may be the hardest discipline. Owners and leaders want to do something, anything, rather than feel uncertainty. Yet action for its own sake can break your own position. You can disrupt your plan before it has a chance to work. There are seasons when the right move is to wait, to gather information, to let pressure build in the right places. Make small, safe adjustments. Watch the field. Protect your king. When the time comes, you will see the trade that looks like a loss but is really an opening. You will know which piece to give away, and which future you are buying with that choice.

In the end, the Immortal Zugzwang Game is memorable because it shows that mastery is not only about what you do. It is about what you refuse to do. Nimzowitsch drew a circle around the future and stepped back. Sämisch had to step forward and into that circle. That is the nature of pressure, in chess and in life. Win the right kind of space, keep your plan intact, and be patient enough to let time work for you.