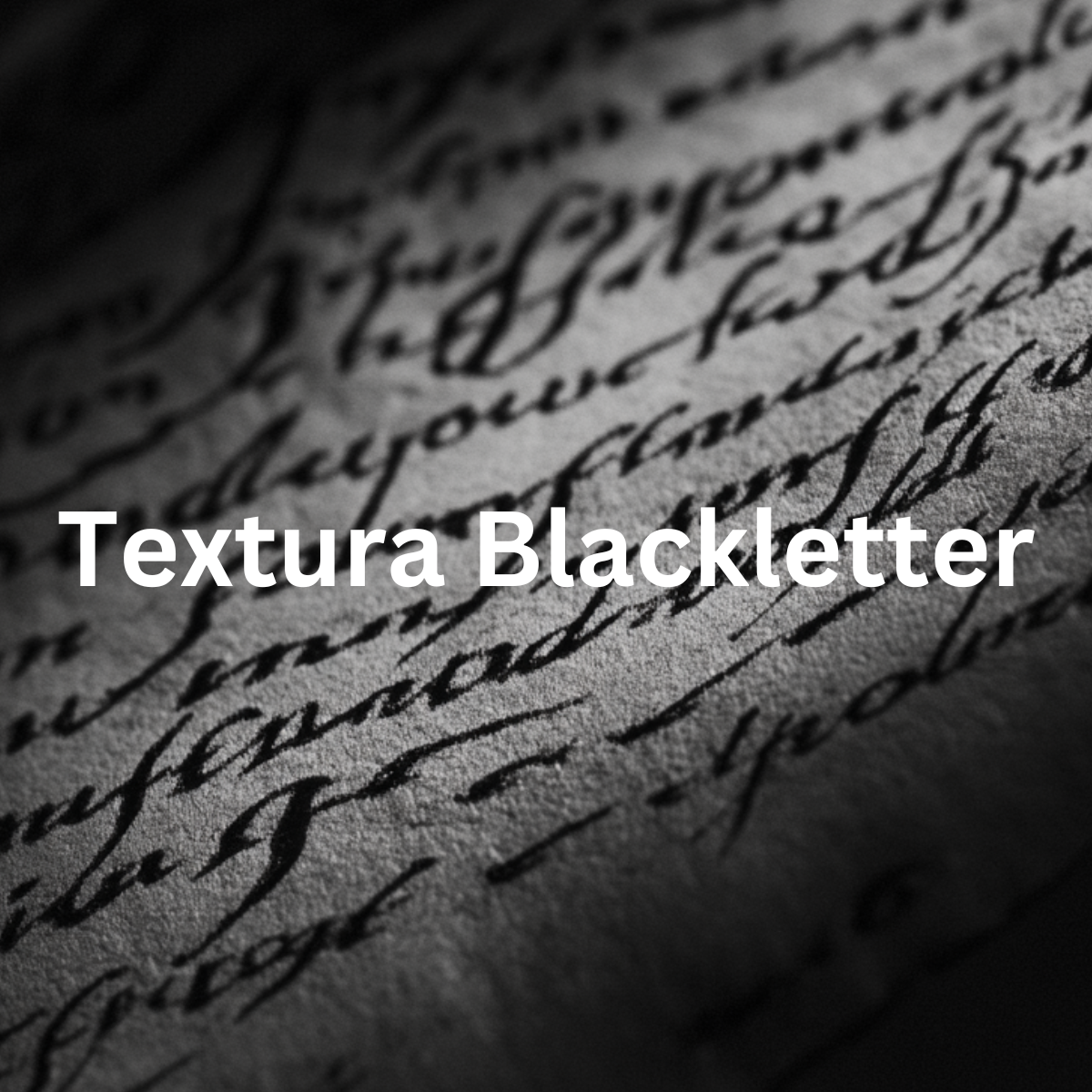

Many of us are familiar with the Gutenberg press, a marvel of human ingenuity that ignited a cultural revolution in the Western world. The first major publication, the Gutenberg Bible, is often heralded as the dawn of mass-produced literature. But what is often overlooked is the script that made this possible—the first standardized typeface: Textura Blackletter.

Before the invention of movable type, written language was largely the domain of scribes, painstakingly transcribing manuscripts by hand, most notably in Catholic monasteries. The elegant, tightly woven letters of Textura Blackletter were a direct adaptation of the calligraphy styles used in these scriptoria. When Gutenberg devised his press, he did not just create a machine for printing—he established a permanent means of replicating language. A typeface. A font. Something that, once set, could be used again and again without human intervention.

Today, we take this for granted. With a simple dropdown menu in a word processor, we can select from thousands of fonts, each one a product of centuries of refinement. But this idea—that language could be reproduced mechanically, separate from human effort—was once a radical concept. In fact, the resistance to mechanical fonts in the 1400s mirrors our own contemporary anxieties about artificial intelligence.

For thousands of years, humans recorded knowledge by hand. Then, suddenly, someone realized that we didn’t need to keep repeating the process. We could build a permanent methodology of reproduction. The very same shift is occurring now with large language models. For all of history, we have structured our thoughts in language, over and over again, passing knowledge from one person to the next. Now, we have discovered a way to codify that process—an architectural blueprint for thought itself.

And yet, just as in the 1400s, we lament. We worry that something precious is being lost. We fear the death of originality, of authenticity. But look at what happened with fonts. The creation of the first standardized typeface did not kill diversity—it amplified it. Where once there were only a few regional script styles, we now have an explosion of fonts, numbering in the tens of thousands. Creativity was not stifled; it was unleashed.

Evolution is often spoken of as a given, a force as inevitable as the rising sun. But how does it actually manifest? We will not grow keyboards embedded in our limbs, nor will a mouse become an extension of our hands. Instead, we adapt to the pressures of our time. We follow those who master the tools that define survival in their era. Today, those tools are written, spoken, and illustrated language. Is it any wonder, then, that advanced minds have built entire models to replicate and refine our linguistic constructs?

Perhaps, instead of resisting this shift, we should embrace it. Rather than fearing a world where all books seem written in the same “typeface,” we should see this as an opportunity. Just as the first printed fonts led to an explosion of creativity, so too can our participation in this new evolution. The challenge before us is not to resist progress—it is to shape it.

So, the question is not whether artificial intelligence will change the way we create. It already has. The real question is: What new typeface will we create next?